The Little Mermaid, part vi

The End.

continued from parts i, ii, iii, iv & v

Ever since the little mermaid had understood that two people could make a child, she had constantly before her mind the image of her child with the prince. The image had shifted and wavered, taking on now this feature, now that feature; now one gender, now another; now a grouping, now a single child; now an infant, now an adult with a child of its own. The prince’s betrothal to the princess did not cause the image to fade. But it changed the flavor of the image from sweet to bitter. Forgive me for my callowness in saying this, for she had never had a child, and neither have I, but her suffering in this was the closest she had come to the great pain of losing a child. It was nothing more than a ghost or reflection of that hurt, but she hurt.

And her hurt was twisted and poisoned by her writhing jealousy of the princess. At first the jealousy was simple, and the suffering flared up most when the prince and princess spoke to each other of the future. But even in her deep pain the little mermaid had enough grasp on reason to acknowledge that there was nothing but justice in their match. The prince had a confused sense of someone saving him; the image of her carrying him to land had been mixed up with the image of the princess nursing him after, mixed together by the force of his physical shock and also the druglike effect of the little mermaid’s own singing. Without both of their aid, he would have died. But without the little mermaid, he wouldn’t have needed either of their help. So she was jealous of the princess, not only of her having the prince, but of her moral luck. If her rival had been a mermaid—if she herself had been a human princess—

We often say that we don’t want to be judged. In many cases saying this expresses exactly a wish for judgment—that God can look into our soul and say we did our best—or that laws of karma might mean our current moral luck is a judgment on our past actions—a wish for almost any judgment at all, so that our actions mean something other than their consequences. The little mermaid had known no better when she killed those men. If she were being judged, that would be taken into account by the judge—or if her predatory nature was her inheritance or sentence for a sin in a past life, it would also be fair. But reality never grades on a curve. In the absence of a judge, it must be said that despite her ignorance, which could in some sense be called innocence, the men were dead, and their families were bereft, and she had hurt the prince too, and the princess never had.

There's some irony in her jealousy, for the princess had lived in fasting and modesty and seclusion, without a taste of meat while in the holy place, while the little mermaid had lived among treasures, spoiled by her sisters, never knowing want til this want for a man. But surely we can sympathise.

Royal weddings have always been diplomatically complicated affairs. Does the ceremony take place in the bride’s father’s land, or the groom’s, or both? It was negotiated that their wedding would take place at sea between the two nations, in another swanlike ship, with a hull that curved like a wineglass, and a lacy white wake that trailed like a wedding-veil, and full-bellied sails quickened by the Western Wind. We will pass over the nuptials, for the little mermaid is our protagonist, and “her ears heard nothing of the festive music, and her eyes saw not the holy ceremony.” She thought only of the first time she had seen the prince, and how then she had it in her power to have him completely to herself, if not to have him completely; to consume him, if not to copy him; now that she had failed in her attempt at the latter, she wished bitterly she had taken the former when she could.

She only came back to herself when she watched the couple disappear hand-in-hand into the stateroom, and she noticed suddenly the smell of orange-blossoms rising on the salty air. Then “she thought of the night of death which was coming to her, and of all she had lost in the world.” Whether the sea witch had told her that “she had no soul and now she could never win one” & that “an eternal night, without a thought or a dream, awaited her,” or whether it was quite the opposite, and she was now doomed to continue the cycle of suffering, when as a human she might have achieved nirvana, she mourned for her soul as well as for her prince.

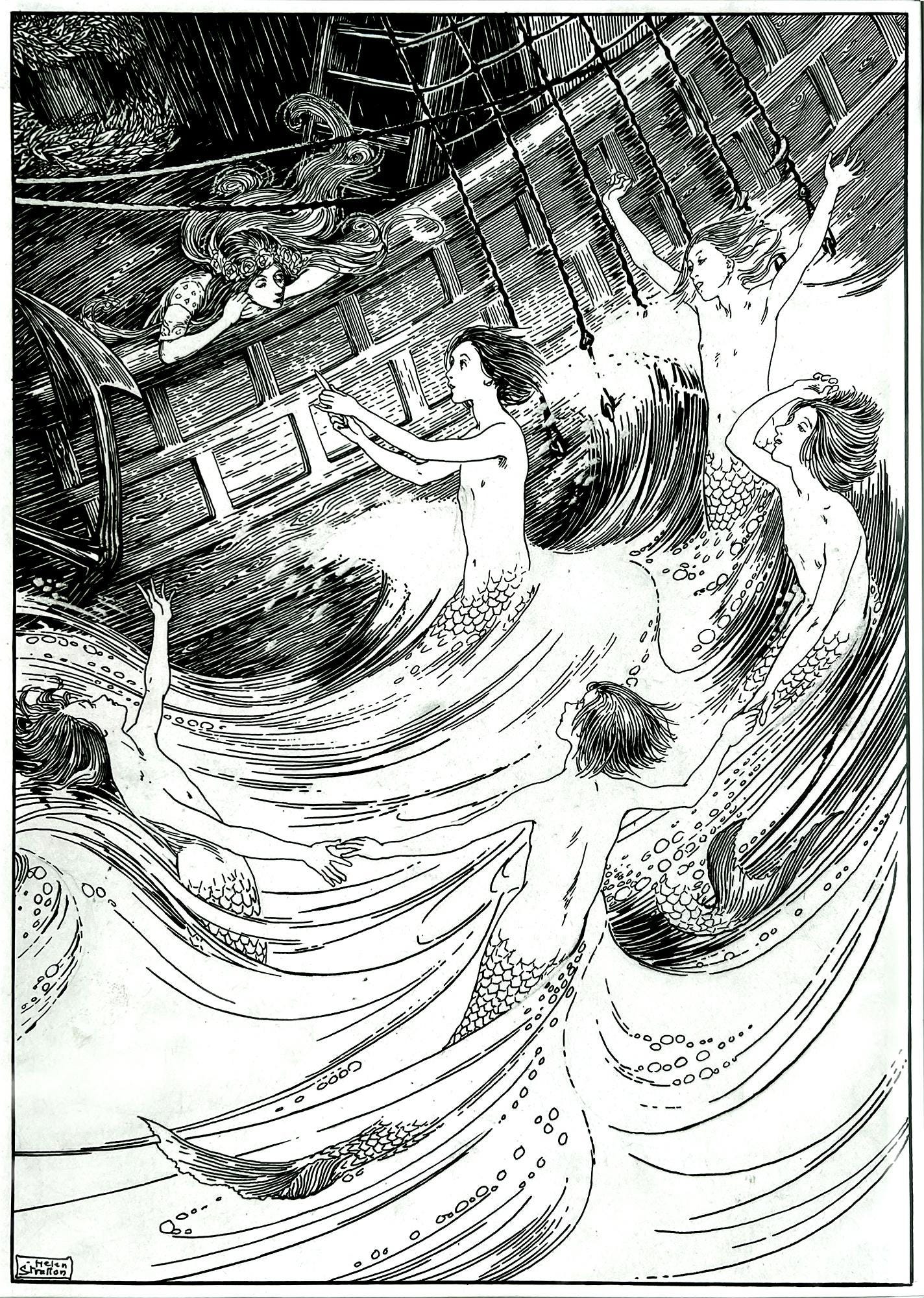

As the last revelers filtered off to their rooms, she did not follow them; why sleep now? Instead she “looked towards the east for the first blush of morning, for that first ray of dawn that would bring her death.” But, to her surprise, before she saw the dawn, “she saw her sisters rising out of the flood: they were as pale as herself; but their long beautiful hair waved no more in the wind, and had been cut off.”

They had traded (though only temporarily, for hair grows back) this much of their seductive power to the seawitch, in exchange for her blessing on the eldest sister’s treasured golden knife. The little mermaid had only to kill the prince with it, and she could join them in the sea again—but she must hurry, hurry, before the sunlight touched her—

The little mermaid crept into the stateroom, where the two lovers slept in each other’s arms. Her eldest sister swam and lept anxiously at the portholes as the little mermaid hesitated. Looking at the knife, she saw how her sisters loved her, but the touch of their love did not make it easier for her to forget her love for the prince. Instead, their love reminded her of other love, that he was loved not only by the little mermaid, but by his family, and his bride, and his kingdom, and that he loved all these people too, and even loved her in his way, and she tried to puzzle out a reason for this love to carry less weight than her sisters’ love. “I was afraid of this,” said her sister. “Please, kill him, kill him, and come back to us. But if you can’t, I bargained with the sea witch that you could kill his bride instead, and earn another chance with him.”

The little mermaid’s eyes filled with tears. This offer was beyond the normal level of mermaids’ altruism. It made sense that they would love her enough to make a sacrifice in order for her to be with them again—but the idea that they loved her enough to make a sacrifice, not for the pleasure of being with her, but merely to know that she was happy with others, moved her deeply. And she knew she could not do less for the prince.

Just as she left the stateroom, the dawn was turning the sea red. She threw herself in, wishing to spend her last moments with her sisters, who tried to grasp her as she dissolved to foam. The golden knife sunk from her dissolving hand, without her eldest sister even noticing the loss of this lesser treasure.

But death was not as the little mermaid had expected. As the morning mist rose from the sea, the little mermaid felt herself rise with it.

The seawitch had been scrupulously honest that she could only stay human by marrying a man. But the witch had also been scrupulously honest in saying she needed love to be saved. And her last act had been an act of great love.

I am just a storyteller, and not a mystic, and can say little of the state in which our heroine found herself. But I know that it was a state of great power—specifically of the power to act on behalf of others: to act so that the men she had killed, and the prince she had loved, and his bride, and their children who looked so much like her hopes for her own children, and even her sisters, could come into bliss. And she must have used this power well, because you certainly don't see mermaids around any more, or hear as much of shipwrecks. But you do see women with heavy hair that ripples like water, and eyes that seem to gaze at you from another world, and bodies as flexible as a fish's tail, as if they are the daughters and granddaughters of mermaids saved by love from predation.

The End.

It's lovely.

I'm impressed at the lil' merm for having that much grasp on reason. Lots of people would deny it and blame the princess.

Likewise I'm impressed at her moral clarity about guilt and judgement — most people I know would either seethe with frustrated entitlement or collapse into a ball of guilt. Might be cheating a bit to give her no moral flaws while also being a reformed mass murderer? It works tho.

The "We often say that we don’t want to be judged." paragraph works so well! I'm wondering what the operative ingredient is. Is it the accurate analysis? The mix of general relevance and relevance to the story?

The ending rings false IMO. Not in the events themselves: the actions are perfectly in character (I had 0 doubt what the little mermaid would do, though I worried the sisters would take matters into their own hands), and the just-so story about why there are no or few mermaids anymore fits perfectly well. But something in the tone just feels empty or saccharine somehow??? Totally unlike your usually thing that feels so incisive and observant and on-point. I know I'm a dickhead, I'm always whining about bitterness and cynicism and when you write something happy then I also complain.

Your story hews close to the Andersen one (except for, you know, the flesh-eating murder detail). Are you familiar with the Undine branch (Fouqué / Henze / Giraudoux)? It's more cynical and character-y in a way I feel like would appeal to you (though ofc that'd defeat the point of writing a fairy tale).