The Little Mermaid, part iv

The Prince.

continued from parts i, ii, & iii; continued in parts v & vi

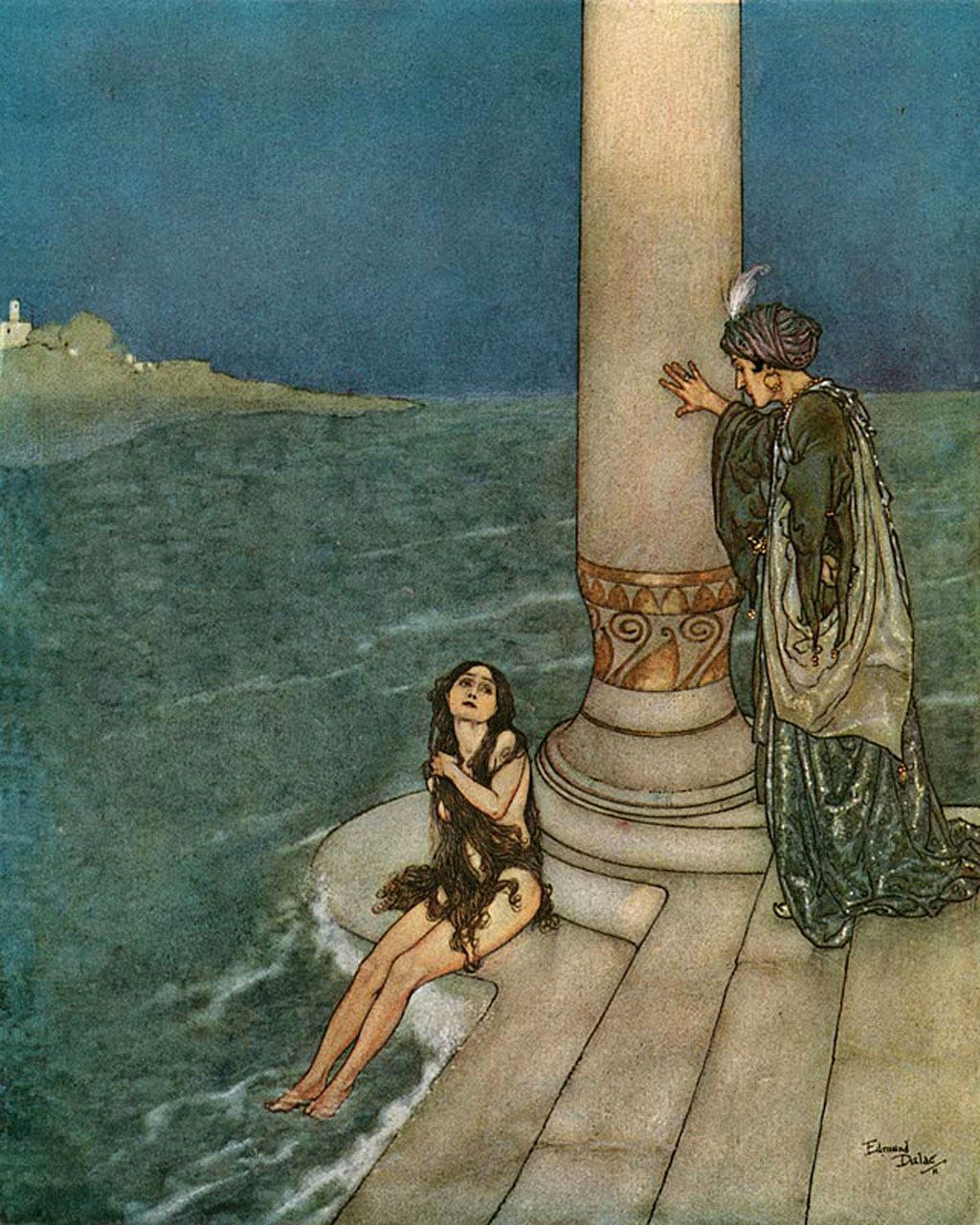

The prince was naturally kindhearted, and had already been well-trained in noblesse oblige and chivalry, so he would have helped any girl in trouble. But his pity was even more moved by this silent stranger, whom he, of course, thought was the sole survivor of some shipwreck—like himself. He attributed her silence to the weight of terror, and grief, and incredulity at her own memories of impossible things seen in the sea, all feelings he knew well.

Certainly her beauty didn’t do anything to counteract his sympathy. As a mermaid, she had been as beautiful as other mermaids, but as a human her beauty was rich and strange. Her long, heavy hair rippled and waved like water. Her long, narrow face seemed always, no matter how close she was, to be gazing in from another world. Her body was as flexible as a fish’s tail.

The prince caught her by both arms to help her make her way to the castle. There, she was washed and dressed by maidservants, and then brought to be presented to the king and queen. Their hall was a great wonder, with its symmetries unlike any sea-cave, its gold and its red, its fireplace and its candles, its tall straight lines and right angles and regular arches. But the king, the queen, & the prince were the greatest wonder of all.

I do not know how mermaids continue their species. Some say that, as the cockatrice is born of a chicken’s egg brooded over by a serpent or toad, mermaids are bred when the seed of drowned men falls upon fish-roe, and that these crossbreeds are as sterile as mules. Some say that of course mermaids have males—but that these creatures are as different from their mates as anglerfish from anglerfish. And those who believe this say further that mermaids neither know nor care anything of their young, and that any parenting they get is given by their strange fathers. And still others say that mermaids do not breed like animals at all, but are the innate intelligences of the sea.

Whichever is true, it is certainly true that the little mermaid had never before seen anything like the trio of the king & queen & prince. She thought at first that they must be sisters, but then knew that they were not like each other the way sisters are like each other, but like each other in some other way, unfamiliar to her. And then the little mermaid knew exactly what she desired from the prince. She wanted to be one of such a three: to be to him as the queen was to the king, and between them a creature like both of them, but even younger and healthier and more dazzling.

The prince told his parents that she had been found washed ashore, and that, emulating the stranger who sang and saved him, he would save this silent stranger. And thus began her time at the court.

“As the days passed, she loved the prince more fondly, and he loved her as he would love a little child,” for he felt he understood her sorrow, and treated her with great gentleness and consideration. Perhaps the little mermaid would have had better luck if he had been a slightly worse person. Though she was very beautiful, he was not low enough to seduce a girl lonely, lost, and mute, with only himself as her protector. He had high animal spirits but would never so insult a virgin, keeping his amours to married women, who had less to lose—and who would expect less from him. But if he had been rash and heartless for long enough to ruin her, he might have afterwards repented enough to make a true woman out of her. Matches are made by this method every day. Meanwhile, his parents were urging him to wed. But he told them he could not love any woman but the one who saved him from the sea. And the little mermaid’s heart leapt when she heard it.

“Very soon it was said that the prince must marry, and that the beautiful daughter of a neighboring king would be his wife.” But the prince begged his parents that there would be no question of his marriage until he had done honor to those who had survived his lost sailors, and to everyone who had lost much to the sea. And of course the little stranger he had found on the shore would be among them.

The castle was decked out for a solemn festivity, and when the little mermaid followed the prince into the great hall, it was filled with many families. But as she followed the prince from one family to the next, as he grasped their hands and spoke to them in low voices, she saw that there was something missing from each. She would see an old couple, but they lacked a son. She would see a mother & children, but they lacked a father. In every cluster or grouping someone was missing.

It may be an example of a certain kind of feminine solipsism—the same solipsism that once led an eminent lady to say that “women have always been the primary victims of war”—that the first guilt that the little mermaid felt was not for the men whose lives she had ended, but for the women who lost them. She knew, as yet, little fear of death, but she knew very well the hollow ache of desire. These women had wanted a man, like she did—had wanted a child, like she did—had been satisfied, as she hoped to be satisfied—and had the object of their desire slip from their grasp, forever, because of her, because of what she had done. She was not yet human enough to weep—mermaids need no salt tears in the salt sea—but she would have wept if she could.

She tried to rationalize away her guilt. Surely the sailors knew where ships sank, and could have avoided the danger! Surely they had heard of sirens, and could bring wax for their ears and bindings for their masts if they might be entering dangerous territory. They wanted to come to her—they chose to jump! But even had all these arguments been very fair and just, and the sailors had deserved it all, she could not say that their survivors did.

The prince saw the suffering on her face and thought he understood it. “I know exactly how you feel. It’s only by senseless luck that I am here and he is not, or that you’re here and your family is not, it’s impossible to understand,” the prince told the little mermaid. And as he consoled each family, as he thanked them for the bravery of their lost son or father or brother, the prince told all of them that she too was a victim of the sea, and had lost everything. Then old women squeezed her hand warmly, and young widows embraced her, and she could not contradict him, and might have been too afraid and ashamed to tell the truth, even if she could.

continued in part v

I'm really enjoying the story. It's so well written and has that enchanting feeling of an old fairy tale, something I haven't experienced in a long time. Looking forward to the next installment!