The Little Mermaid, part iii

The Sea Witch.

continued from part i & part ii; continued in parts iv, v, & vi

Consulting the sea witch was risky. To ask her a question, much less to ask her for help, a mermaid must trade a great treasure. And even that may not be enough. If the witch was unsatisfied with an offering, she would devour the supplicant.

So the little mermaid wrapped her marble statue in a piece of fishing-net, and her worried eldest sister shared the burden with her, stewarding her down deeper and deeper and deeper to a hole near the base of their mountain, which opened to the cave where the sea witch lived. As they descended, the water grew so heavy above them that even their well-adapted mermaid ears ached with the pressure, and light dwindled and faded. When they came to the witch’s door, the little mermaid’s sister squeezed her hand. “If there’s trouble, call for me,” she said. “I brought my treasure too: my golden knife. Maybe it will be enough for her.” But she let the little mermaid enter the grotto alone.

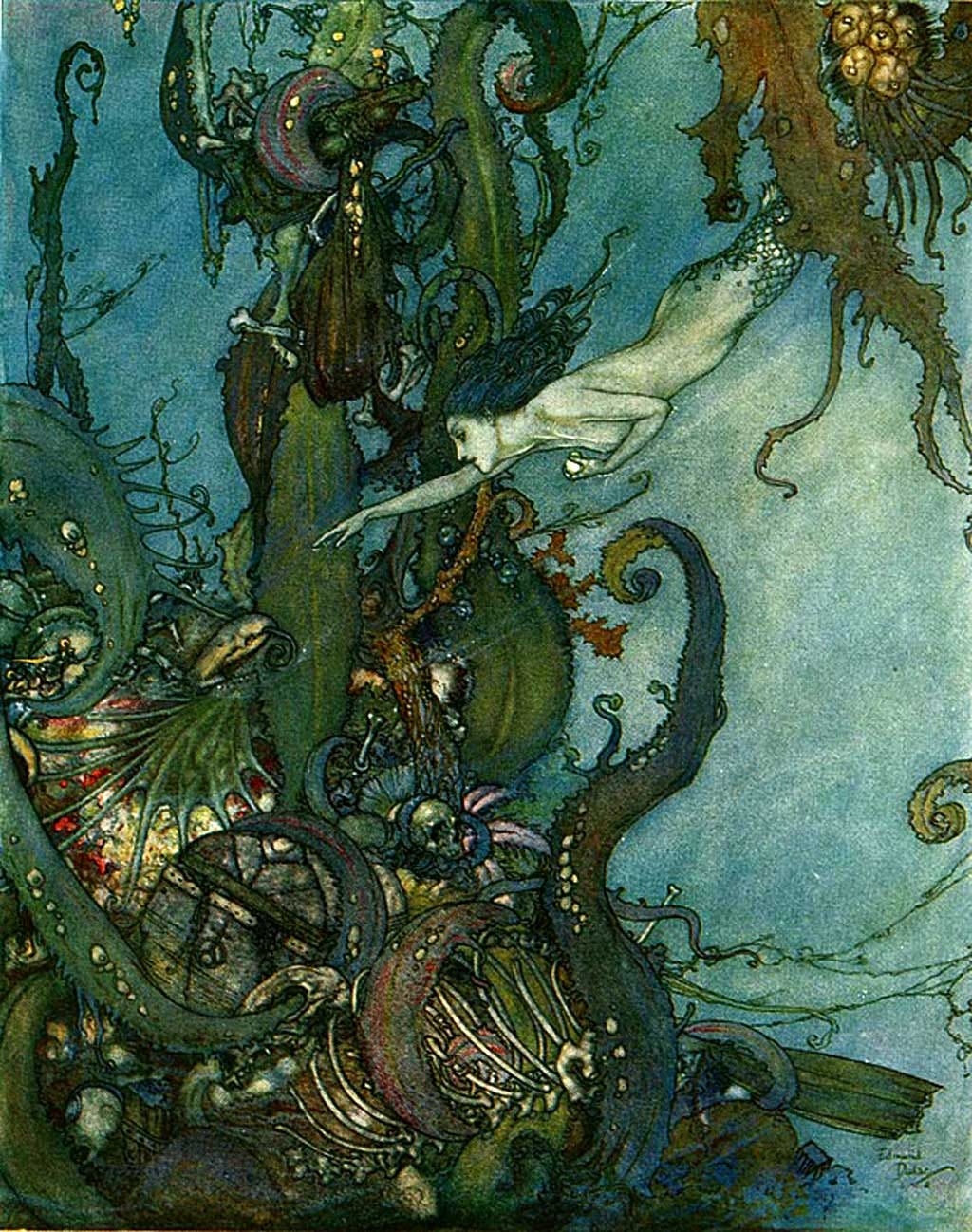

It was not illuminated by sunlight—how could it be?—but by shimmering and winking bioluminescence, clouds of glowing algae or dinoflagellates, herds of jellyfish, here and there an anglerfish or a squid, which from time to time illuminated one or another of the niches carved into the cave-wall, some of which held such great treasures that the little mermaid had never seen the like, and some of which held the jumbled bones of mermaids. Some patches of light below her looked as distant as stars. She felt a numinous dread at the chamber’s depth and size. And now and then a dark shape passed between her and some patch of light. Maybe that shadow was just an animal. But maybe not.

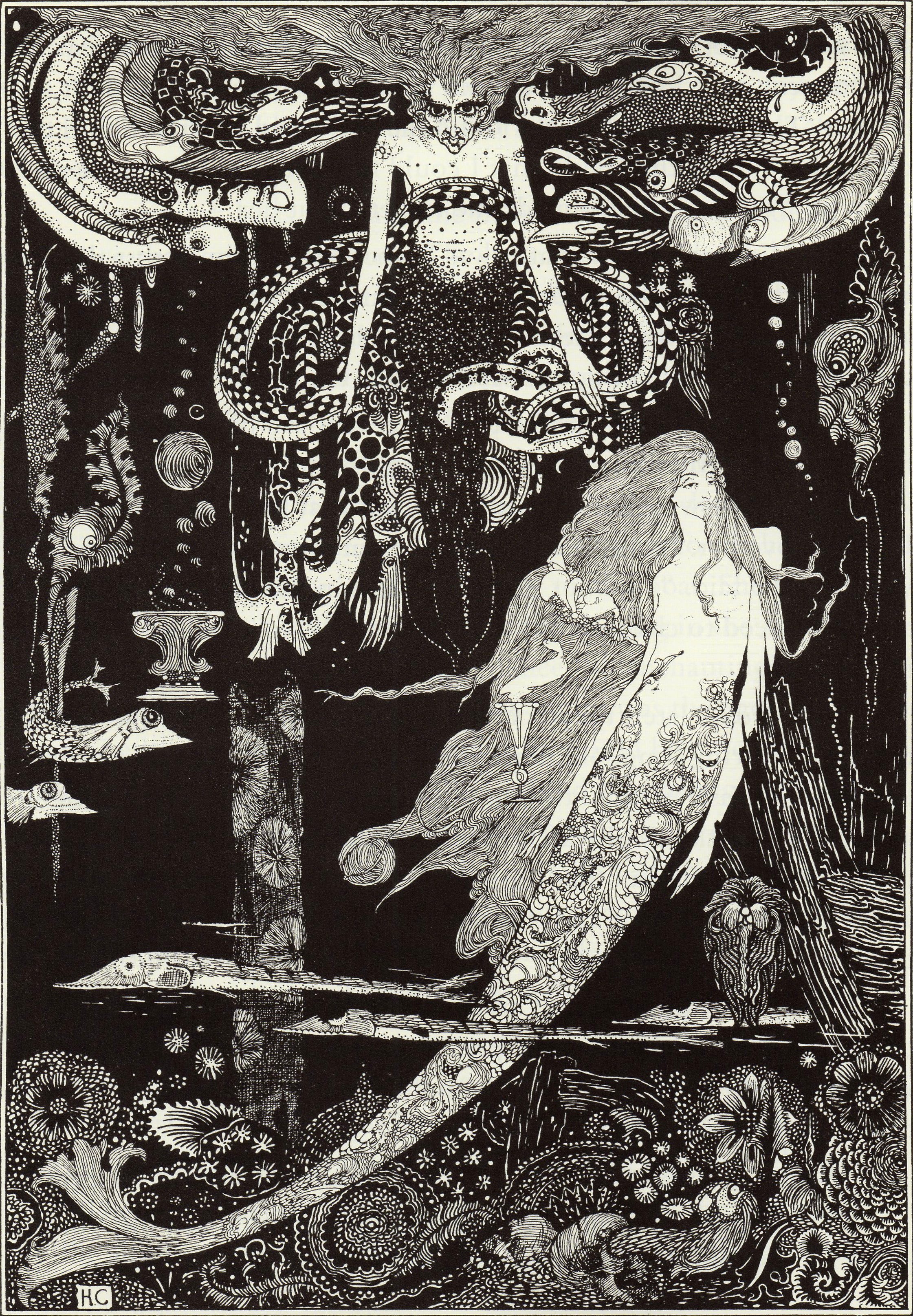

Though the sea witch could not be seen in the huge chamber, her great rasping voice boomed deeply inside it, setting the water to vibration and setting off a wave of frantic flashing among the bioluminescent creatures: “What ails you?”

“I’ve made myself sick with curiosity at the human world, swimming in freshwater and ignoring everything else to watch them, but I have learned so little. I must know what you know.”

“Give me that statue and I’ll tell you.” And though the little mermaid was sharply hurt by its loss, she had been less interested in it since she met the prince. She was ready to trade simulacrum for reality.

I am just a storyteller, neither a philosopher nor a theologian, so I am not sure what the sea witch told her. Certainly she told her that humanity is much shorter-lived than mermaids are. But that disadvantage is more than made up for by this—and here I get confused about exactly what the sea witch said—either humans have immortal souls, unlike mermaids, and can enter paradise—or else quite the opposite, and mermaids will live forever, but humans can exit this world of pain and suffering, and achieve a null bliss. But whichever she said, it had the ring of truth, and the little mermaid envied human fate greatly.

“Well, now you have knowledge, but I doubt that satisfies you,” said the sea witch. And her laugh filled the chamber. “But to ask again, you’ll need to trade again. And I’m not sure I’ll like anything else that you have as much as I liked your sculpture, except maybe your dainty flesh.”

Trembling, the little mermaid unfolded her net a little more, and drew out the prince’s circlet, with which she was even more loath to part than her statue. “I don’t even know what to ask for. Tell me what would satisfy me, what would cure me.”

“Ah!” said the sea witch appreciatively, and a great shape emerged from the depths of the chamber: the sea witch’s hand, with its index finger extended, as big around as a man’s head, for old creatures can grow very large when born up by the weight of water. She delicately put her finger through the crown to wear it as a ring, and withdrew her glinting hand.

“I’ve lived a long time,” said the sea witch, “and I have seen such cases before. I know what you want. You desire humanity, and you desire a man. Fortunately for you, the way to get either is to get both. You need love to be saved. If you marry him, you’ll live as a human. But if he weds another, you’ll dissolve into seafoam the next morning. Either way, you give up your life as a mermaid. If you want to take your chances, I can help you.”

“But I have nothing left to trade,” cried the mermaid, before thinking of her eldest sister’s golden knife. But the sea witch had another idea.

“You have your voice. I have never heard one more enchanting. Trade me that, and I will make you a woman, and give you your chances.”

The little mermaid nodded, and then felt something catch in her throat, and then in her own golden voice, but larger and more resonant, heard the sea witch say, “Then the deal is done.”

She began to feel splitting pain in her tail, and burning pain in her throat, and realized the change had begun immediately, there, in the depths. (When making this kind of agreement, you must pay careful attention to exactly what is agreed to.) She heard her own golden laugh now coming from the sea witch’s throat. When she managed, frantic and hurting, to find her way out of the chamber, her sister asked her anxiously how things had gone, but she could not answer, and her sister saw her changing. Without any more questions, her sister bore her up to the surface, and the little mermaid pointed her in the direction of the prince’s castle, and together they swam to that coast, as the youngest sister slowly changed and changed.

She could not even say goodbye to her sister, who retreated mournfully once she was safe on the sand. The little mermaid was left alone, bereft and naked and battered as Odysseus washed up on the Phaeacian shore—but, like Odysseus, not alone for long, for the prince was pacing the seashore as he so often did, and would notice her soon. For the first time she tried to stand with her two new legs, tottering like a fawn, hurting with her weakness, hollow and aching with desire.