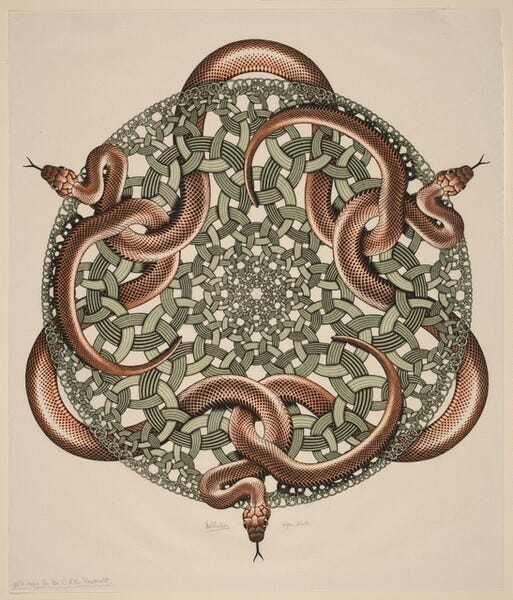

Viper's Tangle

Maybe there’s some sort of law of conservation of literary repression. If only D. H. Lawrence at his obscenity trial could have been given a vision of BookTok! Now when I go into a bookstore, a majority of the volume/shelf space is devoted to mass market novels—how shall we say—characterized by a Lawrentian vitalism; on the other end of the spectrum, novelists win literary awards for what an influencer could accurately map as “sibling’s best friend, spicy, praise kink” content. On the other hand, as Naomi Kanakia points out, contemporary novels (especially with any literary ambition) are squirmily shy about money, something that Austen and Trollope could talk about with unblushing frankness. Literary novelists also seem weirdly shy about redemption. I feel like the most common thing, if the issue comes up at all, is for the story to tease the possibility of redemption and then snatch it away. But redemption, like money, is actually very real. In real life, people get redeemed all the time!

François Mauriac’s Viper’s Tangle came out in 1932. So, it's not exactly a recent novel,1 and it felt even older than it actually was, because by 1932 the trends I’m talking about were well underway.

An old miser, believing he’s dying, writes a long letter to his wife about his plot to disinherit her and their children, his revenge on them for loving his money more than they love him. In the process, he stops desiring the revenge and starts desiring something else.

So. Whenever I try to shill this book, inevitably A Christmas Carol comes up. Which is kind of embarrassing, because people think of childhood and muppets and so forth, but actually I think A Christmas Carol is an eternal golden banger, and that as popular as it is, it’s still underrated.

Viper’s Tangle is French, 20th century, less supernatural (in the sense that it’s realistic instead of magical), and more supernatural (in the sense that it’s straightforwardly Christian instead of suffused with vague Victorian spiritualism), and the money plots are granular and specific almost to the point of tawdriness—something which in contemporary literature you basically only see in mystery novels. It’s also much more concerned with what happens after redemption, with how to integrate redemption.

I don’t know if you’ve ever had a loved one be redeemed, but if you have, then you might agree that it’s surprisingly annoying. For one thing, it makes them unpredictable. You used to know what they would do, and now you don’t. Even when “behaving differently” means “behaving better,” this is kind of inconvenient—and it’s really hard to accept someone else’s redemption, not just because of lack of charity, but because if they fail you again, thinking “same old, same old'“ is less painful than raising your hopes and being disappointed.

But there is also a lack of charity. Sometimes even though you could deal with their unredeemed self, their redemption provokes severe resentment. “They have worked but one hour, and thou hast made them equal unto us, which have borne the burden and heat of the day.”

Mauriac doesn’t end the book with Monsieur Louis’ epiphany; he has to deal with this distrust from his loved ones, even as his new love and openness to them makes him more vulnerable than he has been in many decades to suffer from their distrust of him.

Those that would know say that redemption feels like dying. When writers try to externally dramatize this death-to-self, they often fuck up in the direction of making the redeem-ee into a pod person, totally parasitized by a happy smiley sanctity which is totally discontinuous with their previous personality. Mauriac knows better. His redeemed Monsieur Louis is still a prickly, cynical, analytical old lawyer. But at least one of the characters sees that his analytical prickly cynicism has something different behind it. There’s a moment where one of the characters is suffering severely. Everyone else is trying to being sweet and consoling; when Monsieur Louis tries to connect with her, he does it from his own (naturally and habitually) prickly character—the other comforters see it as him scolding her. But she sees that he’s being totally authentic with her, and that he really sees the regrets she has, which everyone else is trying to convince her have no validity. The closeness they build afterwards is fraught, frustrating, difficult, and transformative for both.

To me, anything within the last hundred years counts as contemporary, which I’m not saying to brag about how widely-read I am in old books, but to confess how poorly-read I am in recent ones.

100% agree Christmas Carol is great, needs more love.

That said I will brook no tolerance of this willful slander of Kermit the Frog. Muppet Christmas Carol is the best adaptation, better than the book, fight me.

https://thedispatch.com/newsletter/frenchpress/remembering-what-repentance-looks-like/

The best essay I've ever read on the topic of redemption. He mostly warns of the dangers that come from allow redemption to be weaponized, and illustrates it with an example.

"None of this service was performative. None of it was designed to pave the way for his return to public life. Once he lost the public trust, he never attempted to gain it back.

The irony is that he did in fact recover that trust. In 1975 he was awarded a CBE for his charitable work, and in 1995, he sat at Queen Elizabeth’s right at a dinner..."