The Unfacedoxxed Egirl in Literature

Contains spoilers for unspoilable classics

I’ve been working on this on and off since like January and haven’t been satisfied with it. I’ve shown it to two other people who I believe politely avoided telling me it was kind of schizo. Also, I’m not sure how much it works if you haven’t read the books/poems in question. And it falls apart towards the end. Frankly I am not sure what you can get out of this as an audience, but I have been thinking a lot about this, so now you also have the option to think about it.

As I go about my life, I often wonder, “What the fuck am I doing?” This, I think (hope), is pretty normal. What is not normal is the paucity of options to address this feeling. The most historically normal thing for people to do, when they don’t know what they are doing, is to listen to stories of what other people have done. But a lot of the stuff I am doing, I think a lot of the stuff most people are doing now, is highly mediated by the internet. There are a lot of stories about (& on) the internet, but they suffer inherently from a flaw that makes them much less useful than stories generally are, which is that they’re unavoidably pretty new. We just cannot know yet 1) how things will play out for people longterm & 2) which stories will resonate longterm. There is also a non-unavoidable problem with stories about the internet, which is that of the literarily-ambitious ones I have read, basically all of them suck. (If you have read a literarily-ambitious & actually good story about this new life of ours, PLEASE let me know.)

So I find myself lost, as maybe you do, in this largely storyless1 void, trying to make decisions without the kind of information that is maybe evolutionarily normal for people to have, or something. But often I find myself surprised, when reading some old book, by finding a narrative or situation that unexpectedly mirrors some aspect of online living. That’s how I felt reading about, for instance, William Temple & Dorothea Osbourne.

One thing I do, that is enabled by the internet & is extremely strange historically, is interact a lot with people who cannot see my face.2 Even this is pretty weird, given that writing hasn’t been around very long, but even more historically-strangely, I can interact more or less instantaneously (like, normal conversational speeds) with people for whom I have zero physical presence, not even the suggestive height/volume/movement conveyed by a burqa, not even the breath & shadow behind a purdah screen or a confessional. Another weird aspect of this situation (which is kind of highlighted by my examples of hidden people in the last sentence, examples of hiddenness that are pretty like institutionalized/rulebound) is that I decided to do this. I feel basically okay about this decision, I can see the ways it’s working out for me so far, and the tradeoffs that present themselves so far, but I don’t like the feeling of navigating something without a comforting safety net of stories about it. It makes me realize how little it’s true that any of my decisions, especially the satisfying ones, come directly/uncomplicatedly purely from inside me, & also how little I want them to, how much I would rather have that like social embeddedment.

So in this state of largely storyless frustration I have been very surprised and pleased to encounter a feeling of recognition in a few great old stories. A feeling, specifically, that I was somehow reading “about” the unfacedoxxed egirl. So I wanted to write about these stories. In writing about them, I have also had to think about them. I found a lot of stuff that was in some sense expected, that I already knew, and I also found that in the process of reading the stories with a productive mindset, trying to write about them, trying to tell y’all clearly what is happening, I noticed a lot of stuff my reading eye had glided over before (often disturbing/troubling/prediction-muddling).

The main thing these characters will have in common is that they cover their faces. But they have ended up having a lot of other traits/symbols/themes in common. I don’t know if that is because this is what veiled women are like in literature, or if this is because these are the stories that happened to resonate with me.

The Lady of Shalott

Most of the “unfacedoxxed egirls” we’ll talk about below are storytellers, creators of mediated narratives. But only one of them is really a doomscroller. The Lady of Shalott is interesting because her story focuses more on consuming mediated narratives at the expense of reality, and trying to make the switch from mediation to reality. The Lady is under a mysterious curse that will doom her if she looks out of her window, so instead she spends her time watching it all pass by in a mirror, & making a second reflection of this reflection by weaving everything she sees into a tapestry—till one day she sees Lancelot pass by, and turns from her loom & mirror to look at Camelot. The still-mysterious curse comes down on her: her tapestry flies away, her “mirror crack[s] from side to side,” the mediated life is no longer available to her, and (with “a glassy countenance” replacing her cracked mirror) she lays herself down in a boat & sings herself to death, floating down the river to Camelot. Everyone comes to look at her corpse, wondering & fearing; only Lancelot says a prayer for her.

The Shakespearean Crossdresser

In writing about Rosalind, I realized that none of these Shakespeare characters actually fit the archetype that all the other ladies in this essay do. The main thing that made me put them in the “unfacedoxxed egirl” bin in my head is that they pass so easily as boys. I’m a little sad about this lack of fit because I was going to call them “roman towelboy types” & now there isn’t really a place for that phrase.

Orual

Orual is interestingly the only one among these characters who is unambiguously not beautiful. That is why she hides her face the first time—her father is remarrying, he orders the bridal party to wear thick veils so Orual doesn’t scare his new queen, “and I think that was the first time I clearly understood that I am ugly.” (Yes, she’s the narrator; the conceit is that she is writing the story as an accusation of the gods, to be brought out of her country to Greece, “where there is great freedom of speech” & they can discuss whether she’s right or wrong. Orual is highly parasocial: she was brought up reading Greek literature/science/philosophy, finds Greeks superior to her own people, wants these strangers for an audience.) Then she veils a couple of times for convenience on adventure. But it’s about halfway through the plot that she takes on the veil permanently. She describes her decision as “a sort of treaty made with my ugliness.” I’m not so sure I believe her. Why does she decide to take the veil exactly then? She’s been ugly the whole time.

When she veils herself for good, Orual has just (unintentionally?) ruined the life of the person she loves most in the world. A pleasing symmetry: what she did, specifically, is convince her beloved sister Psyche to break a promise to her new husband & look at his face, which he has kept hidden from her. Orual does not, at this point in the book, express guilt over this. In the clash between the modern, high-realism, highly psychological style of Till We Have Faces & the dream logic of the myth it retells, I think the reader doesn’t find her guilty here either. But I do think she’s hiding her face because of what she has done, not what she looks like.

Like many hidden-faced women—Bradamante, Britomart, Eowyn (whom I won’t be discussing because I haven’t read LOTR…)—Orual is a warrior.

I’m obsessed with how Lewis presents the social consequences of veiling. Instantly, some strangers start treating Orual like she’s beautiful; pretty soon people also start treating her like she’s scary. “No one believed [the veil hid] anything so common as the face of an ugly woman.” Another insightful bit: “…all men knew the veiled Queen. My disguise now would be to go bareface; there was hardly anyone who had seen me unveiled.”

The book has a bunch of other characters who at least sometimes hide their faces. Brides go veiled (surprise), the priest of their fertility cult wears a birdmask during rituals, the sacred prostitutes in the temple wear wigs & have their “faces painted till they looked like wooden masks.” Psyche has her face similarly hidden with makeup when she is taken to be sacrificed, & the idol of Psyche which we encounter late in the book is veiled in black through every fall & winter. And of course there is Psyche’s husband, & the veiled judge who appears in her final vision. Face-hiding for others usually seems to function as subsuming an individual in a ritual role—I’m arguing with myself about whether the same holds true for Orual, who becomes queen shortly after veiling…when she dreams that her father is back, “all the long years of my queenship [shrink] up small like a dream,” & she spends the dream unveiled….

Her unveilings:

She goes to see the wife of her dying military advisor, who’s deeply resentful of how hard Orual has worked her husband. Orual tears off her veil to show her ugliness, & it is in that moment that the wife realizes for the first time that Orual has been in love with her husband.

Not long after, she goes out in the disguise of her bare face, planning to drown herself. A god orders her to stop, & she does.

In a vision, Orual is brought to the court of the gods to make her accusation against them. She is stripped of her veil & then the rest of her clothes. after her case comes to a close, she is brought to see psyche’s challenges. When she herself appears among psyche’s challenges, she doesn’t recognize her own face. Then, by the edge of a reflecting-pool, she meets her sister. When she looks down at their reflections, both are now beautiful.

Mentioning the reflecting-pool brings me to something I hadn’t been thinking about when I started writing this, but find myself noticing in more & more of the stories: the recurrence of mirrors. I feel a little silly for not having already picked up on this; obviously a story where faces are important enough to hide is going to have mirrors, or something?

Boiardo & Ariosto’s Bradamante

I haven’t read Orlando Innamorato or Orlando Furioso but this Bradamante is the basis of both of the next two characters. She’s a lady crusader hiding her gender as a man in her suit of armor, she falls in love with an especially chivalrous Saracen, reveals herself to him, adventure tears them apart but they reunite, etc etc etc. Mostly listing her here for context for the next two subsections.

Britomart

Britomart is Spenser’s allegorical representation of the virtue of chastity, but she’s not the little milksop you might expect from that description. She’s a tsundere tomboy gf in a suit of armor. She feels unbelievably modern, hating needlework like Arya Stark; the biggest difference between her and the modern “strong female character” archetype is that she doesn’t have the dreamworks-smirk personality, but instead is as courteous & civil as a knight should be (which doesn’t preclude her having a temper or being extremely difficult—but when she’s acting as a man & a warrior, her behavior is at the standard set for the other warriors).

Britomart’s journey begins when she looks into an enchanted mirror &, instead of seeing her own reflection, sees a handsome young knight named Artegall & falls desperately in parasocial love with him. To seek him out, she dresses in armor (helmet on, face hidden) & goes out fighting—Merlin has told her that her handsome knight is the only man can defeat her in battle, as is proper for the embodiment of militant chastity. So she seeks him out by fighting every man she can, actually meeting him in a disguise of his own & defeating him once along the way (I guess Merlin said he could beat her, not that she couldn’t beat him).

The scene where he finally does defeat her is one of the great cinematic moments of poetic history. In the heat of battle, Artegall cleaves Britomart’s helmet, almost killing her—and revealing her face just as he raises his sword for the final blow. She’s flushed & sweaty & panting from the fighting. Love at first sight.

I like that Britomart likes to fight. It’s a lot more fun & less complicated to fight with the helmet on.

Calvino’s Bradamante

We’re not discussing Bradamante as she may appear in Calvino’s retelling of Orlando Furioso because it hasn’t been translated into English yet. Very sad as I am desperate to read it.

In his fabliau The Nonexistent Knight, she appears as the other kind of unfacedoxxed egirl. Before he ever catches a glimpse of her face, her lover falls for her when he sees her splashing in the water after a battle, armed from her waist up, nude from her waist down. Goodness gracious!

Like many after her, she makes the trad heel-face turn & lives under a new name as a nun, & we discover that she’s writing the story we’re reading…..there’s something I love so much about the repeated “veiled narrator” trope…..

Esther Summerson

Writing this section was a little bizarre: I have read Bleak House so many times, and always taken Esther’s meek & retiring self-presentation very straightforwardly. Only rereading it with a bit of a mission showed me how weird and dreamy & illogical & Jungian the actual sequence of events that occurs to Esther is.

Both unfacedoxxed & pseudonymous (literally, with regards to her last name—who are her parents?—but also hinted at in her first name, the pseudonym of a queen). Moreover, possessed of poster mindset: she writes at least “[her] portion of these pages,” the first person-POV chapters of Bleak House, & I like to play around with the belief that she wrote the third-person parts as well. She’s a shy little thing who “had always rather a noticing way…a silent way of noticing what passed before me” (also attesting to poster mindset). Raised by a godmother, “like some of the princesses in the fairy stories,3 only I was not charming,” she says of herself, she’s in kind of a daddy longlegs situation with a mysterious benefactor.

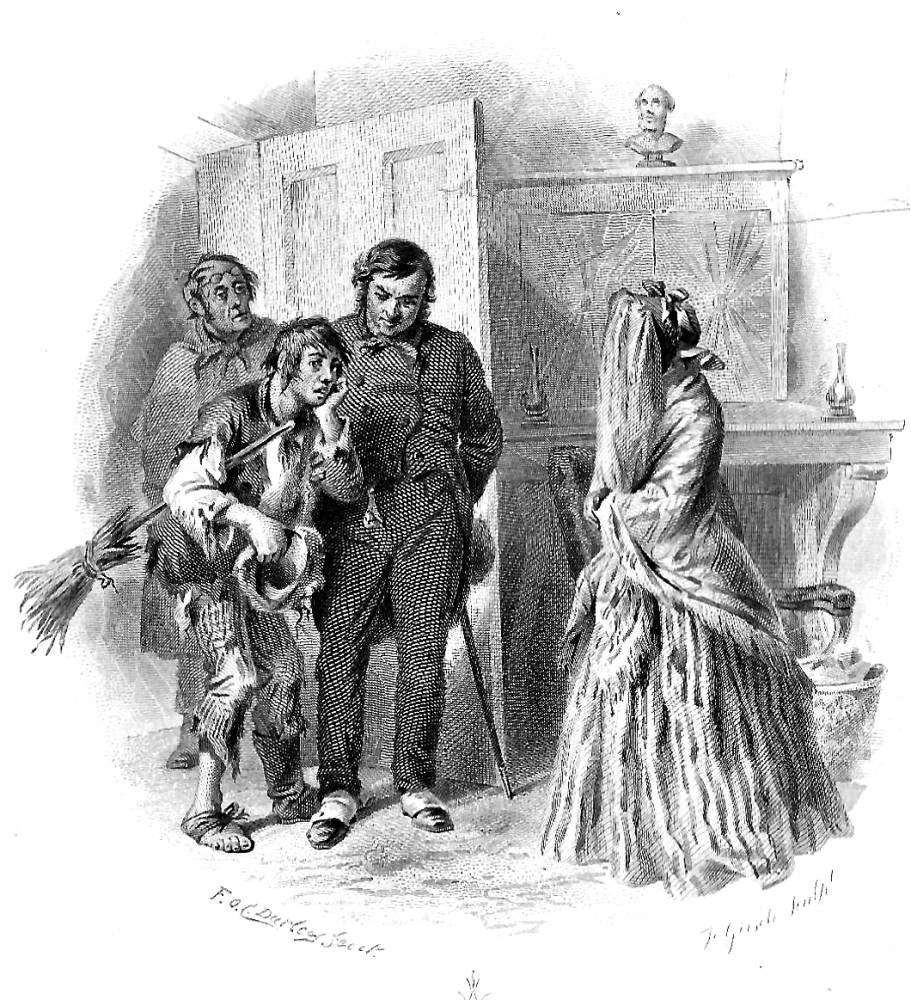

Esther’s case is interesting because she takes the veil about halfway through the book, coincidentally just before—and I had to double check this several times, because I was sure it was going to be after—a long, DMT-trippy battle with smallpox leaves her pitted and scarred. Like, she puts on a veil for some reason, after we’ve never seen her do so before, & while wearing the veil she meets a dying urchin boy, who infects her maid, who infects Esther as Esther cares for her. Even more coincidentally, the orphan boy mistakes her for another veiled lady who took him to a graveyard; when Esther shows him her face, he says there must be three of them then. She finds herself part of this fate/furies/norns/weird sisters-like trio of veiled women.

She has three really great unveiling scenes.

In the first, an old friend (seeing her for the first time since her illness) calls her “always the same dear girl,” & she pulls up her veil a little; when he repeats that she’s “always the same dear girl,” she puts it up all the way. One of the most important things here is the precision of her memory of exactly what happened, compared to the ambiguity & uncertainty of the third unveiling scene.

In the second, she visits the home of a totally ridiculous & full-of-shit guy whose proposal (before her illness!) she had gently rebuffed—rebuffs he’d refused to accept as final. She shows her face, & he responds with disgust & an attack of hypochondria, dizziness and coughing, “dear me—something bronchial, I think—hem!”4 She reassures him that she asks nothing from him but that he stop investigating her origins: she knows who her parents are. She shows her face and knows her name.

As it turns out, the first veiled lady was her mother, who bore her secretly to a man who himself now goes by the Odysseus-like pseudonym of Nemo (Latin for no one) & then married sir Leicester Dedlock, acquiring a new name and rank herself.5 She’s described as drawing “her habitual air of proud indifference about her like a veil” as well, she’s always veiling one way or another.

The third unveiling scene occurs when Esther runs into the man she has long been in love with (is she barefaced here? She’s afraid of him recognizing her). She gathers up her courage, puts “my veil half up—I think I mean half down, but it matters very little” (why isn’t she sure now, when she remembered the same detail so precisely in the first unveiling), and goes to see him, fully unveiling after they talk a little.

By the end of the book she’s finally organized herself under a single name—importantly, neither her father’s nor her mother’s nor the false name she was given, but her married name. It ends with an ambiguous scene where Esther’s husband assures her she’s more beautiful than ever; she’s not certain she agrees. She’s been so insanely low self-esteem & self-deprecating throughout the book that you want to think this is more of the same, but one can’t be sure.

Out of place, because I hadn’t noticed this before, hadn’t accounted for it, & thus haven’t figured out a way to integrate it into the structure of what I’m thinking about: mirrors. I weirdly hadn’t noticed the recurrent use of mirrors in Bleak House (or Infinite Jest) until writing this—the way they showed up in the Lady of Shalott & the Faerie Queene primed me, but it’s kind of strange that it hadn’t occured to me otherwise. We have Esther looking into a mirror in chancery court in the beginning, “not that it’s requisite, I’m sure,” as Esther’s smarmy suitor says…we have Lady Dedlock “be, in a confused way, like a broken glass to me”

Madame Psychosis/Joelle van Dyne

I feel a little trepidation about even approaching this one. Infinite Jest is, as you probably know, very long. And unlike everything else I mention here, I haven’t read it in years. Also it is one of those ambiguous stories for which summaries are untrustworthy. So even though I’ve been control-f’ing “Madame Psychosis,” “Joelle,” “P.G.O.A.T.”, “veil,” “mirror,” extensively to refamiliarize myself with what actually happens, I’m not sure I can stand behind my interpretations on this one. There is a lot I could have missed.

Basic info: Madame Psychosis is the stage name of a cult radio personality, whose face is hidden not only behind the faceless medium of radio but behind another layer of screens and veils. The other main name she is known by is Joelle van Dyne, which sounds like a birth certificate name, although it is occasionally claimed otherwise. She was at least at one point extremely pretty, and it’s ambiguous what is under her veil now—debilitating beauty, or a face marred by acid?

Two great quotes:

She had a brainy girl's discomfort about her own beauty and its effect on folks, a caution intensified by the repeated warnings of her personal Daddy.

The twirler was so pretty that not even the senior B.U. football Terriers could summon the saliva to speak to her at Athletic mixers. In fact she was almost universally shunned. The twirler induced in heterosexual males what U.H.I.D. later told her was termed the Actaeon Complex, which is a kind of deep phylogenic fear of transhuman beauty.

Why the veil? A third party, interviewed about Madame Psychosis/Joelle van Dyne, tells this story. Joelle’s father confesses to “being in love” with Joelle; hearing this, her mother reveals her own history of molestation at the hands of her own father. The mother announces that she is going to stop hiding what a monster she herself is for recreating this system. She grabs a vial of acid, which at first the reader thinks she is going to use to disfigure herself. But then she throws it. The acid is, supposedly, intended to hit Joelle’s father, who ducks. But the acid-to-the-face doesn’t particularly make sense as a punishment for incestuous urges, and it does make sense as a solution to a face so beautiful that it could “cause” such incestuous urges. Not long after, Joelle’s mother kills herself, taking with her the secret of whatever intentions she acted with, leaving behind only their consequences.

It’s probably not a total coincidence that this unfacedoxxed egirl is showing up in a book that is also largely about Alcoholics Anonymous. Because like. Anonymity. There’s also the U.H.I.D., “you hid,” the AA-style Union for the Hideously and Improbably Deformed, which Madame Psychosis attends.

She’s the only one of these unfacedoxxed egirls who stays unfacedoxxed. We never find out what is under that veil.

Something interesting I noticed rereading: the mirror that shows up immediately before the acid-splashing scene. Joelle’s father is secretly watching her have sex with her college boyfriend in her childhood bedroom through the bathroom mirror. So, like Britomart’s mirror, or the Lady of Shalott’s, or the mirror in the Romance of the Rose, this mirror functions not to show the viewer’s actual reflection, but to reveal a love-object.

Authoresses

Lots of them. The Brontë sisters, Austen at first, George Eliot sorta, George Sand sorta, James Tiptree Jr….

General Traits of the Woman Hiding her Face and/or Name

Often a warrior

Often a writer or storyteller or image-creator in the story. very often the narrator. I wouldn’t have predicted this, but it makes sense: if you can’t see her, how does she exist in the story to be known at all, unless you hear what she has to say?

Often living a parasocial/mediated life

Often highly malebrained

Usually beautiful

Usually facedoxxes eventually

Mirrors

Food for thought.

or—maybe this is more accurate—inhabited by larval, incomplete stories?

The thing is that my other option, as an online person, is to interact a lot with people who can see my face while I cannot usually see theirs. This is not really more normal. So I have chosen one of two pretty weird options.

Cinderella & Sleeping Beauty were both anonymous to their princes

Just before this, he’s kissing the note she sent him to let him know she’s coming—I wonder if that’s why he feels so sick?

The third veiled lady was Lady Dedlock’s cast-aside & vengeful maid.

I re-read the Lady of Shallott recently and also saw a tragic e-girl angle to it.

Before the mirror cracks, she is kind of emotionally dulled. She's not unhappy, really, but living a limited emotional existence. "She lives with little joy or fear," but through the weaving the mirror image, she experiences bursts of excitement. ("But in her web she still delights / To weave the mirror's magic sights.") This isn't joy, but some other kind of incomplete pleasure that leaves her perpetually underfufilled. This is all that she seems to be driven by: "no other care hath she."

The Lady of Shallott archetype seems more like a girl who is in an environment where she is coasting through her emotions by getting basic psychological needs met, but not able to progress past that. This reminds me of people who spend years of their lives being entertained by the Internet, especially through lurking and other parasocial activities, who eventually feel as though they have little to show for it. Instead of building skills, relationships, etc., they feel like they just drifted through time without progress.

The cracking of the mirror is the culmination of her fomo. The mirror (half-existing on the Internet) no longer feels gratifying, but integration into the real world feels unfathomable.

I don't know what Tennyson's original idea was here. There's an alternative take on the "blissful ignorance" of female domesticity (she is complacent while ignorant of her own lack of independence, and upon realizing how she is restrained, she cannot handle the frustration). But I feel like the Lady of Shallott being absorbed into the emotional hibernation of a solitary Content Consumer seems to work for some reason.

I'm now re-reading this a few hours after first coming across it. I probably should have written a comment then, when the associations were still fresh.

First, this is probably not what you meant by literarily ambitious stories, but what came to my mind immediately when I read that phrase is the almost-a-genre of fanfiction that's broadly a modern AU where one or more of the characters are writers/involved with the literary world somehow. They're usually quite meta. Examples:

Les Misérables:

https://archiveofourown.org/works/1060639/chapters/2126196

Merlin:

https://archiveofourown.org/works/387876 (AO3 account required)

Supernatural:

https://archiveofourown.org/works/18083927/chapters/42744872

I, uh, have read all of those far too many times.

(Also, I remember you mentioning a writing workshop? What might qualify one to join?)

Your essay, and some of the stories referred in it, resonated with me a lot. I'm not entirely sure I know why. Maybe it's because I've been scouring the internet for comprehensible-to-me information on social dynamics, and I've noticed that once I find a writer in that domain, one of the things I'll do relatively quickly is try to find a picture of them, to figure out how attractive they are. I'm not sure how accurate that perception is, but it seems like an important piece of information to conceptualize someone's opinion on social stuff. Maybe that's just my recent preoccupation with the subject though (I fixed a chronic health problem I didn't know I had, got a bit more attractive as a result, and am struggling to update my social scripts).

Wrt being unfacedoxxed, I suppose not having the information about someone's attractiveness status creates space for people's assumptions and projections, letting the veiled person experience a different dynamic than the one they're normally privy to. Growth experience, "walking a mile in someone else's shoes", maybe?

Relatedly, it's been observed that being (very) attractive isn't always an advantage. I think it was Simone and Malcolm Collins who pointed out that having an attractive girlfriend is such a source of validation for teenage boys/young men, they're unlikely to risk losing the relationship if she engages in suboptimal behaviour. Which might not be good conditioning for the woman.

In this context, the veil trope might be a narrative device to have a beautiful character that also has virtues one might learn growing up without the advantage of good looks? (Humility, kindness,...,?) (I'm not sure I'm explaining this well.) (An alternative device would be to come up with a plausible reason why she grew up ugly, or similar - an unattractive person has to learn how to be likeable without people being primed to like them.)

One thing I'm having trouble parsing is the warrior/malebrainedness thing. Like, is being seen as attractive woman a hindrance to achievement in masculine domains? (I don't trust my observations on this.) One alternative hypothesis I can come up with (not sure if I agree with it) is that it might be a male (malebrained person's) fantasy of having a partner they don't have to struggle to understand (not femalebrained) but who [strikethrough] has boobs [/strikethrough] possesses feminine beauty.

Anyway, thank you very much for writing this, it's definitely food for thought!