The Six Swans & the Silent Sister

I have a great weakness for fairy tales about girls who can’t speak. There aren’t as many as I would like, though, which is one reason why I wrote one. The main ones I can think of are The Little Mermaid, and the slightly lesser-known story The Swan Brothers, which I’ll tell you now:

Once upon a time, there was a family of seven children: six boys and one girl. Though her place in the birth order isn’t mentioned, any sister with only brothers is in some sense an eldest sister, and certainly our heroine proved this. Their father the King had, despite severe reservations, and in very strange circumstances, recently wed a stepmother: somehow, he had become lost in his own woods, and an old woman had offered him help on the condition that he marry her beautiful daughter. He kept his promise, but (knowing the cruelty of stepmothers, as the children told each other when they trusted him—or wanting to leave his old family behind and start over, as they thought to themselves when they did not) the King hid the children of his first family in a castle in the woods.

Like most women who want to marry kings, the stepmother wanted the next king to be her son. If she had only had one or two stepsons, she might have just waited it out and hoped for a tournament or a hunt, a battle or a fever, to turn fortune towards her line. But with six boys already in the order of succession, the stepmother would have to take action herself, which she was very capable of doing. She found their hidden castle (this probably shouldn’t have been too surprising, given that her female line had wrangled a queenship by knowing a lot about the woods) and gave her six stepsons six magic shirts, which turned them into swans.

This story must have happened in a Salic land, where only men can inherit, because the stepmother didn’t bother to transform her stepdaughter. The woman did effectively disarm the girl, though: the curse was such that the girl could only break it by keeping her silence for the six years it would take to weave six magic shirts out of asters which would turn her brothers back into men. As is so often the case, she could talk about the problem, or she could fix it.

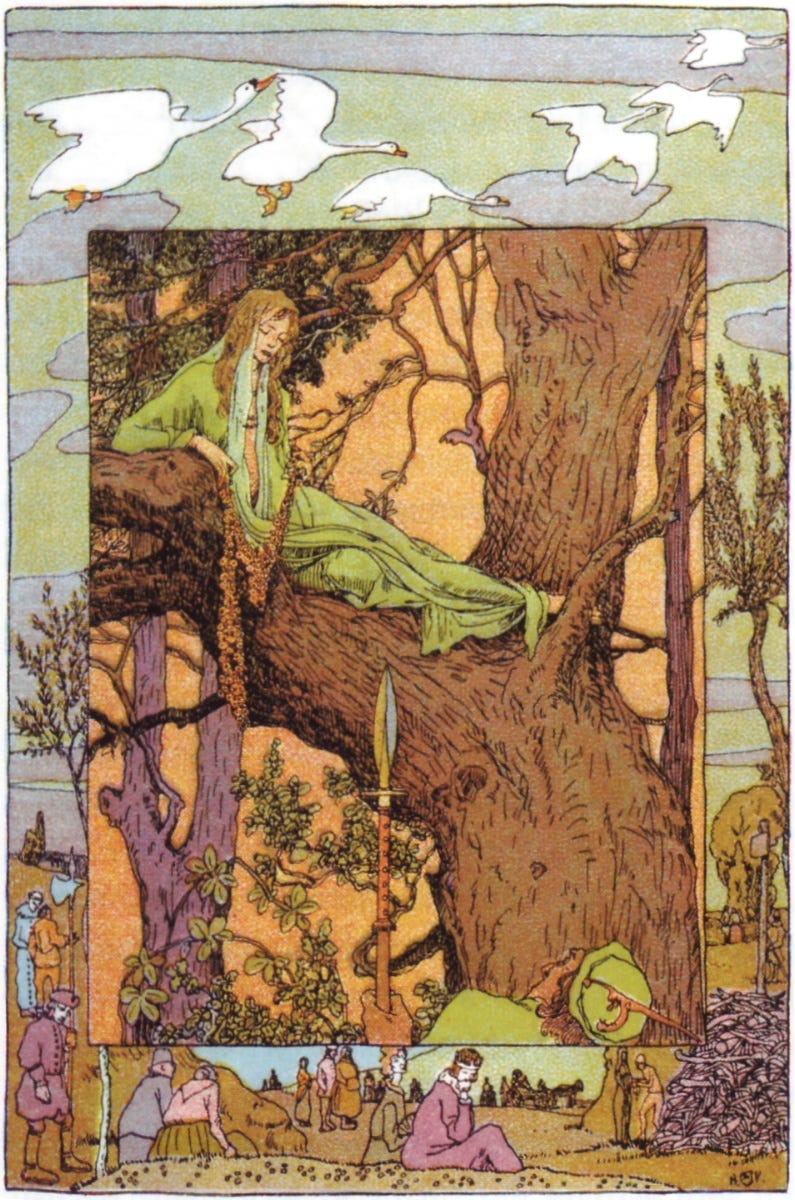

The sister took on the challenge. In the woods she picked wild asters and wove them, in the weirdly beautiful words of the wikipedia page for this story, “dedicat[ing] herself solely to gathering the star-flowers and sewing the shirts in silence.” But early in the fourth year, another King, the young king of a distant country, also found himself deep in the woods, where he saw her, loved her, and carried her away to his castle to marry her.

Her new mother-in-law1 is not crazy about this. Very reasonably, from my perspective, she wonders what is going on with this girl: why the muteness? Why the aster shirts? She suspects the girl of witchcraft, which makes a lot of sense in the world of this story, where it is established that odd shirts can be used for malevolent purposes. But her son the King will not hear her out. Like many boymoms, she is deeply hurt by finding that sex is enough to make a young woman more important to her son than she is. Like many people with real concerns that go unaddressed, she becomes obsessed with making other people see her concerns, even if it means doing some sketchy things herself. This is an explanation but not a justification for her next action. When the young Queen quickly becomes pregnant, not crying out even in birth, the Queen Mother steals her child and accuses the young Queen of killing and eating it.

The King doesn’t believe her, but obviously it doesn’t occur to him that his mother took his child. So in year five, the young Queen gets pregnant again, and the same thing happens; during year six, the young Queen gets pregnant yet again, and the same thing happens. By the third time she has a child disappear and doesn’t even attempt to defend herself, the Queen Mother’s accusations outweigh the King’s love, and the young Queen is sentenced to execution.

Even on the steps of the scaffold, she’s still weaving the aster shirts. She’s on number six, working on the left sleeve. But then, just as she is tied to the stake, just as the pyre is about to be lit, the six years are up. Six swans soar towards the place of execution, and the aster shirts transform them back into men (mostly—the youngest brothers left arm remains a swan’s wing, because of the unfinished shirt2) and the young Queen can finally testify in her own favor. Her three children are found, and the Queen Mother is sentenced to burn in her place. But everyone else lives happily ever after.

My mother really, really hated this story. She felt that it was extremely wrong of the young Queen not to do whatever she could to save her children.3 On the other end of the trad-prog spectrum, there is an obvious available reading that this story is problematic because the young Queen, unable to speak, could not say no. I also feel bad that the mother-in-law gets punished with an intensity that seems to belong more fairly to the stepmother.

I’m not sure just what it is about this story that made me ask for it over and over again as a kid, what makes me like it enough to retell it now. But, having read some Freud, I see some wish fulfillment in the curse of silence. I get a little tired of words, and specifically tired of convincing people. When I feel like I have to, it’s easy to dream about being unable to.

Maybe interesting: in a lot of languages, and even in the English language at other times, there’s no distinction between the word for a stepmother and the word for a mother-in-law

This doesn’t prevent him from becoming a great knight.

In the young Queen’s defense, the kids probably would have been sent out to be fostered by peasants til they were toddlers anyway, which I’m assuming is what the Queen Mother did with them. So maybe it didn’t make that much of a difference to them.

I love this. “As is so often the case, she could talk about the problem, or she could fix it.”

There is also Cordelia in the first act of King Lear, who I think about a lot, though it isn’t exactly a fairy tale.

Does Echo & Narcissus count? Seems like it ought to be a more common motif but I can't really think of any others...