On Literary Allusions

Humility, Worldbuilding, and (as always) the Case against Self-Expression

Y’all really want me to post a 2024 reading list. I’m not saying this to brag. The disproportionate interest in this question—I’ve never had more than one or two people ask me to write about anything else in particular—obviously, hilariously means, “I think that the writing you read is probably much better than the writing you write.” And, of course, I agree.

I’ve spent the last couple of years trying, frustratingly slowly, to rederive writing skills and standards from scratch. (As you’ve probably noticed if you’ve been around for a while—thanks for putting up with this.) Right now I’m stuck on how to handle making literary references and allusions. In workshop responses, or in Claude’s responses to my work (suspiciously convergent, jsyk), references/allusions often get marked with, “Feels pretentious.” But from the inside, when I quote someone, what I’m feeling is not pride. If I’m thinking about myself, it’s more like, well, I’m not going to say it better than this. And in the best case scenario, I’m not thinking about myself at all, but making references as one should bring you cowslips in a hat Swung from the hand, or apples in her skirt, I bring you, calling out as children do: "Look what I have!–And these are all for you."

It obviously doesn’t come across this way. There’s a review of Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You (there, you hyenas, that’s something I read last year, go read that instead)—which ironically I cannot find to cite, if you know which one I’m talking about please let me know—which is pretty withering about her heavy use of references and especially about her bibliography. Said something like—tellingly—“She doesn’t want to be a novelist, she wants to be an academic.”

But the schism between storytelling and scholarship is a very recent rupture. The idea that self-expression (disgusting phrase—like draining pus from a wound) is not only a tool you can use sometimes, a material you can work with sometimes, but the point of writing, is probably the major cause of writing block: “Accordingly, the mask becomes a token of everything you are, even if everyone knows it’s just a mask. Suddenly, the game isn’t fun anymore.” 1

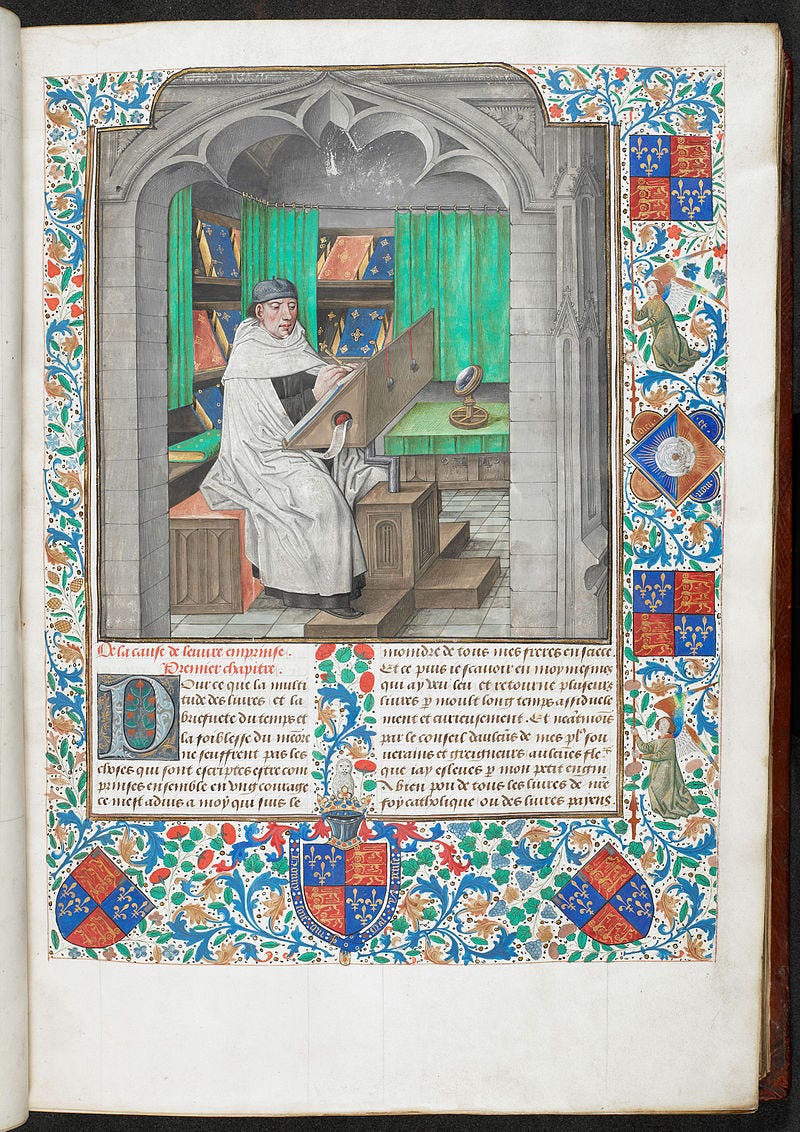

In The Discarded Image, C. S. Lewis describes the charmingly feudal literary culture that produced the strange, foreign poetry of medieval Europe, so unexpected to modern readers in both its trippiness and in the immediacy of its sensory detail, the cinematic or even TV-writing way it uses gesture for characterization:2 “Every writer, if he possibly can, bases himself on an earlier writer, follows an auctour…The writing is so limpid and effortless that the story seems to be telling itself. You would think, till you tried, that anyone could do the like….The telling is for the sake of the tale…Far from feigning originality, as a modern plagiarist would, they are apt to conceal it….For the aim is not self-expression or ‘creation’; it is to hand on the ‘historial’ matter worthily; not worthily of your own genius or of the poetic art but of the matter itself.”

Something that’s funny about this: as when Lewis defended allegory to midcentury scholars, he’s describing a literary technique which was really unpopular then, but which is coming back now: “We should think it ‘cheek’, an unpardonable liberty, half to translate and half to re-write another man’s work. But Chaucer and Malory were not thinking of their auctour’s claims. They were thinking—the auctour’s success lay in making them think—about Troilus or Launcelot.” I’m sure you’ve seen people repeating the now-tired trope that classic literature is actually fanfiction! This probably helps you understand something about literature the first time you encounter it, but after about the hundredth time hearing it, it actively obscures understanding, not only of what Dante and Chaucer et al were up to but what it’s possible for literature to do.3

Let’s look at worldbuilding. You google “Harry Potter worldbuilding” and the results are all, is Harry Potter’s worldbuilding bad?, J. K. Rowling’s lazy worldbuilding, Harry Potter and the Trouble with Worldbuiling, actually the worldbuilding in harry potter is really bad, Rowling’s inconsistent worldbuilding. At the same time, it’s obvious that readers love Harry Potter as much as they do, which is a lot,4 largely because of the worldbuilding. What’s going on?

Right now, the fashion is to think that worldbuilding is good insofar as it’s internally self-consistent. This is great if you’re J. R. R. Tolkien, who basically invented this approach to fantasy. But most people who try to do what he did do not succeed to the extent he did. Most fantasy worlds are thinner, and they fail to achieve the internal self-consistency they’re going for—partly for want of talent, partly because almost no one spends as much time developing their worlds as Tolkien did—and they’re less evocative, for those same reasons and another one. But this is not the only way to write a fantasy!