Instagram Versus Reality

I said it shorter on twitter but here we are anyway

A few years ago a friend showed me an eating-disorder-coming-out-post by one of her favorite influencers. The “during the ed/after the ed” body diptych (a staple of the recovery posting genre) looked weirdly the same on both sides; the influencer was practiced enough at posing/lighting/outfits (& I was unpracticed enough at looking at those pictures) that the body difference didn’t seem that big to me.1 My more experienced friend could point out differences in posing and staging that indicated bigger changes. She thought the post was inspiring, and very brave.

Not long after, she took me to her gym to lead me, glancing at her phone, through what remains the most arcane and complicated workout I have ever done. I got confused enough by her instructions that I was like, “Look, let me just see the workout.” And, of course—although it was so unexpected to me I felt a little vertigo—we were doing one of the influencer’s old workouts. Like, from her eating-disorder days.

I felt weirdly shy about asking, but I am pretty sure that she found that old workout because of the eating-disorder post, & I am more-than-pretty-sure that we were doing that workout on that day because of the “during the ED” pic on the coming-out post. Whatever my friend’s actual intentions were, & whatever the influencer’s actual intentions were, the ED-awareness post had led us to her ED content. I feel now like that’s one reason that eating-disorder-coming-out posts (especially when, like this one, they include stuff like precise dates & weights & pics) are so memetically successful: because they lead people directly to eating disorder content without the content itself having to have eating-disorder-markers on it that will be punished by censorship. That censorship being, like, algorithm censorship obviously, but also internal censorship that tells you, “Is it not fucked up to look at this?”

I’m hardly the first to notice that anti-eating-disorder/eating-disorder-awareness content often functions to reproduce eating disorders; the interesting thing to me here is how a pattern happens (I’ve seen how it plays out in women-spaces more often than in male spaces, I have no opinion on whether it works the same in both) where women will identify ways that social media makes them miserable, & in response, memes will spring up that on a surface level seem to validate & even soothe the misery, but structurally function to keep you on the app, doing the same thing, exactly the opposite of the surface message.

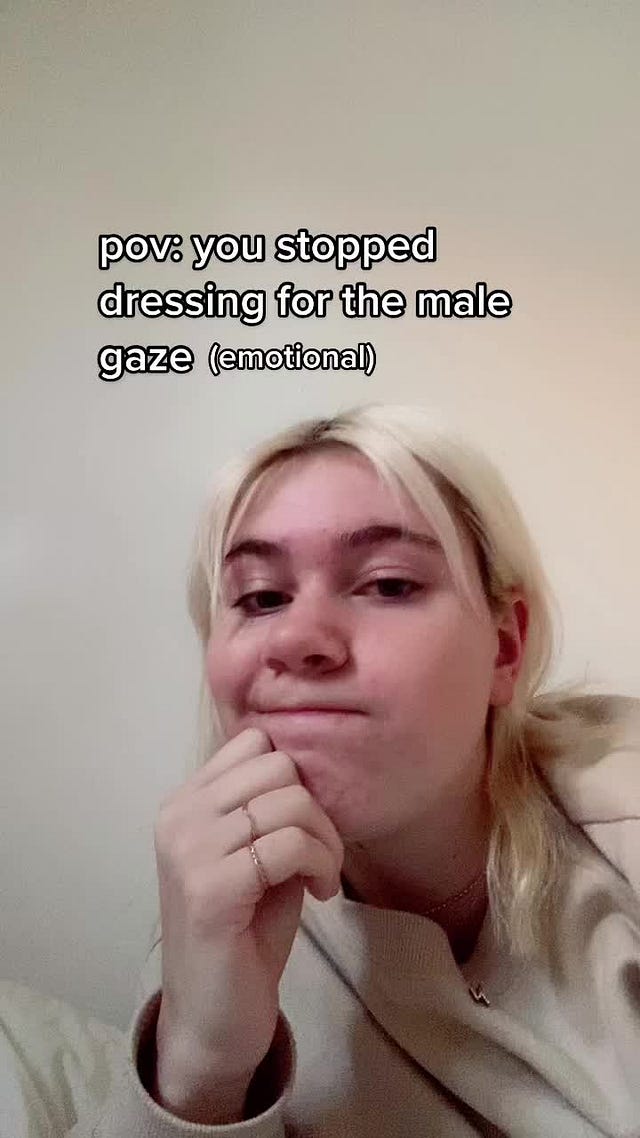

“pov: you stopped dressing for the male gaze” was a tiktok trend in like 2021 that struck me as so odd it continues to occupy my thoughts long after anyone who actually participated in it has probably forgotten about it. This example is obviously a joke but the structure is still there. It spawned lots of discourse—“this meme is so slutshamey,” “this isn’t male gaze vs female gaze, this is 2016 fashion vs 2021 fashion,” “do you know what POV means”—but I don’t think anyone mentioned the (to me, annoyingly transparent) fact that the meme allowed people to project feminist moral superiority on the surface while continuing to get attention and clout for looking sexy in their old male-gazey outfits. They were almost definitely not thinking of it like that, the trend succeeded because it got both lustful eyeballs & feminist eyeballs without the posters ever having to think about the lustful eyeballs, but how did they not think about it?

(A friend points out that modesty-posting on rw girl twitter works the same way: drawing attention to something specifically by means of a claim to hide it.)

The same goes for the “instagram vs reality” thing.2 (If you’re not familiar, the structure of this meme is a maximally flattering image next to a (not usually maximally) unflattering image of the same person, usually the poster, usually with a caption about social media and body positivity.) Obviously, this allows you to get attention for your great, carefully-staged “unrealistic” pic without acknowledging that aspect of what’s happening. Another weird thing is that these memes quietly function as a pretty effective teaching tool for taking “unrealistic” selfies. The side-by-side thing contributes to this—if your selfies tend to look more Reality than Instagram, you have access to a direct comparison that shows you exactly what to change, and usually if you can’t figure it out from the photos the caption will tell you.

The captions often include a message that comparison is bad, you shouldn’t compare yourself to social media, comparison is the thief of joy etc etc etc. But obviously, two side-by-side pics kind of unavoidably prompt comparison with each other & oneself.3 Just kind of a silly little thing.

The most insidious part of the “instagram vs reality” meme is that it redefines reality. One could imagine (though this wouldn’t scale obviously) doing an instagram vs reality comparison by looking at a photo & then looking at the subject in real life. What the meme does, though, is take two pictures and define one as reality. On the surface the message is, “pictures are fake, social media is fake, step away from it,” but the thing it’s actually saying is, “You have access to reality through a screen. We can give you access to reality without you having to look up.”

I have had the same problem the other way around looking at “lifestyle change” (=euphemism for weight loss) body diptychs too

Another meme that peaked years ago, in like 2019, but is still around, & which I contend is influential enough that it shaped how people think of social media still. The current instantiation is probably “posed vs unposed”

I’m trying to imagine what could work better as anti-comparison training, & I feel like the best option might be like meditating on a super beautiful picture of a woman that also has real artistic/aesthetic value, something that’s beautiful not just evo-psych-wise or beauty-standards-wise but has a little sehnsucht in it, just learning to enjoy beauty for itself without reference to yourself…..& then maybe one could bring that attitude back to your social media experience?

An alternative: what people really want is the bad thing packaged with plausible deniability. The stop dressing for male gaze was not aimed at feminist eyeballs at all. It was all hot outfits, all the way down: the consumers just wanted to be able to tell a story it was about something else.

It's like how news channels will try to run tape of attractive people in little clothing if it can possibly get away with it.

I think your dating for people on the spectrum post sort of gets at this idea: the bit about how looking unattainable gives more license to women to dress sexier. I think the plausible deniability might be a sort of epistemic hygiene thing that people value. Or you know some illicit, forbidden appeal. I can totally see that as being hot in a rape fantasy style.

I knew a girl who did a bunch of Instagram stuff while she was a model. Her raciest post by far was ostensibly a story about how a photographer propositioned her metoo style and she said no but was uncomfortable. But it was (especially in the context of knowing her irl) very clearly just an excuse to post the lingerie.

side A 🤝 side B

legitimizing

the A/B

dialectic