Contra Scott Alexander on Taste

Good taste is the capacity for pleasure, and the discernment to find it.

In Friendly and Hostile Analogies for Taste, Scott Alexander asks:

Many (most?) uneducated people like certain art which seems “obviously” pretty. But a small group of people who have studied the issue in depth say that in some deep sense, that art is actually bad (“kitsch”), and other art which normal people don’t appreciate is better…. So what does it mean to say someone else is wrong?

In one of the analogies, as an aside, he says something telling:

It’s not immediately obvious why you would want this skill [ie, taste] - it makes your life worse, because you’ll just be fretting over flaws you see in everything.

This makes sense in a world where everyone experiences exactly the same quantity of exactly the same things, so “taste” can only mean “being picky” and “disliking most of what you encounter.” But the world doesn’t work like that. Actually, some people are much more interested in some field of art than most people are. They’ll interact with more work in that art form, and they interact with each of those works more, and spend more time scouting the art for works they like (and they’re more likely to be working in that art themselves). The obvious reason is that these people are getting more pleasure out of that art form than most people do. They will also often think that some “art which normal people don’t appreciate” is better than some art that normal people do appreciate, and that some art that normal people like is actually terrible—but it’s also true that when they agree with normal people about some work of art being “good,” the normal people are getting less pleasure out of it than they are.

Because I can’t speak for, like, Derek “Die, Workwear!” Guy, I have to do something very tacky: personally declare myself to have good taste in something—in this case, literature—and compare myself to the majority of people that I think have bad taste in literature. A 2022 Gallup poll has American reading a mean of 12.6 books per year; this distribution has a long tail off to the right, and the median American reads five books or fewer. I don’t keep a books-I’ve-read list, but I just went through my borrowing history for the year on Libby & counted the books I read through for the first time. So far this year, 40 (again, not counting physical books, books I reread, books I read on Project Gutenberg, books I downloaded elsewhere). Revealed preferences indicate that I probably enjoy books more than the average American.

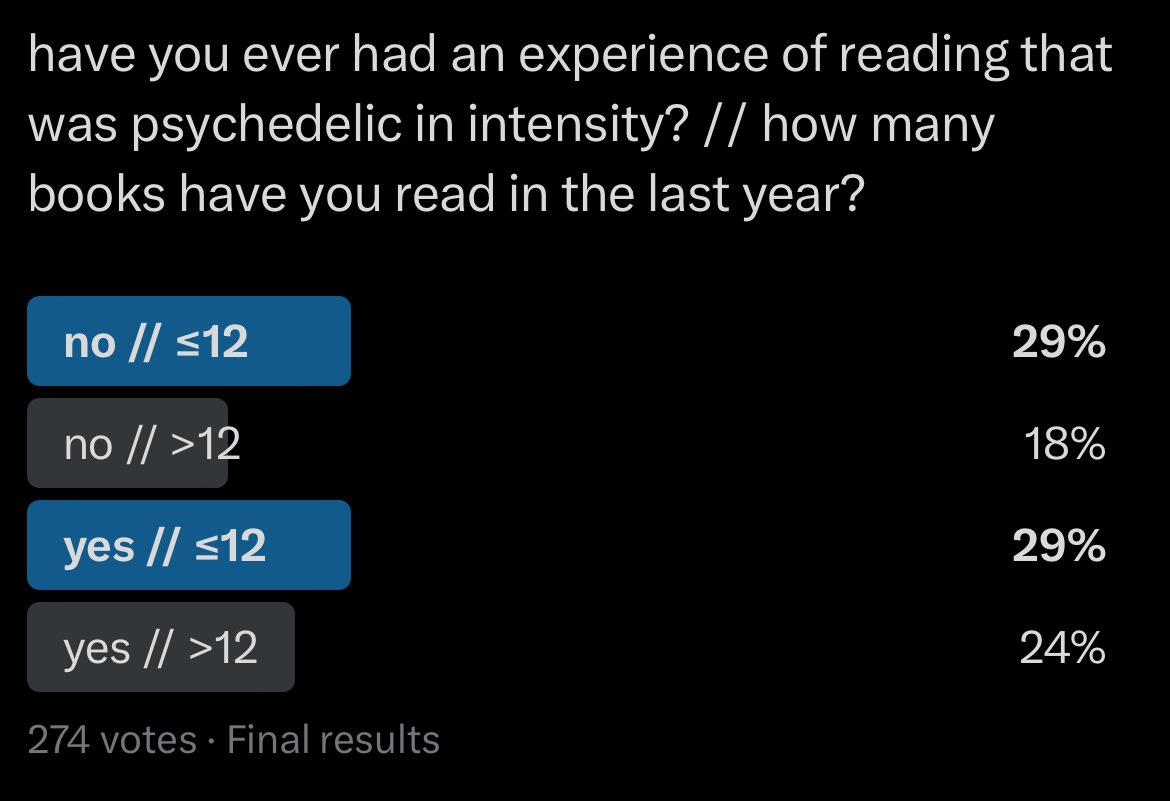

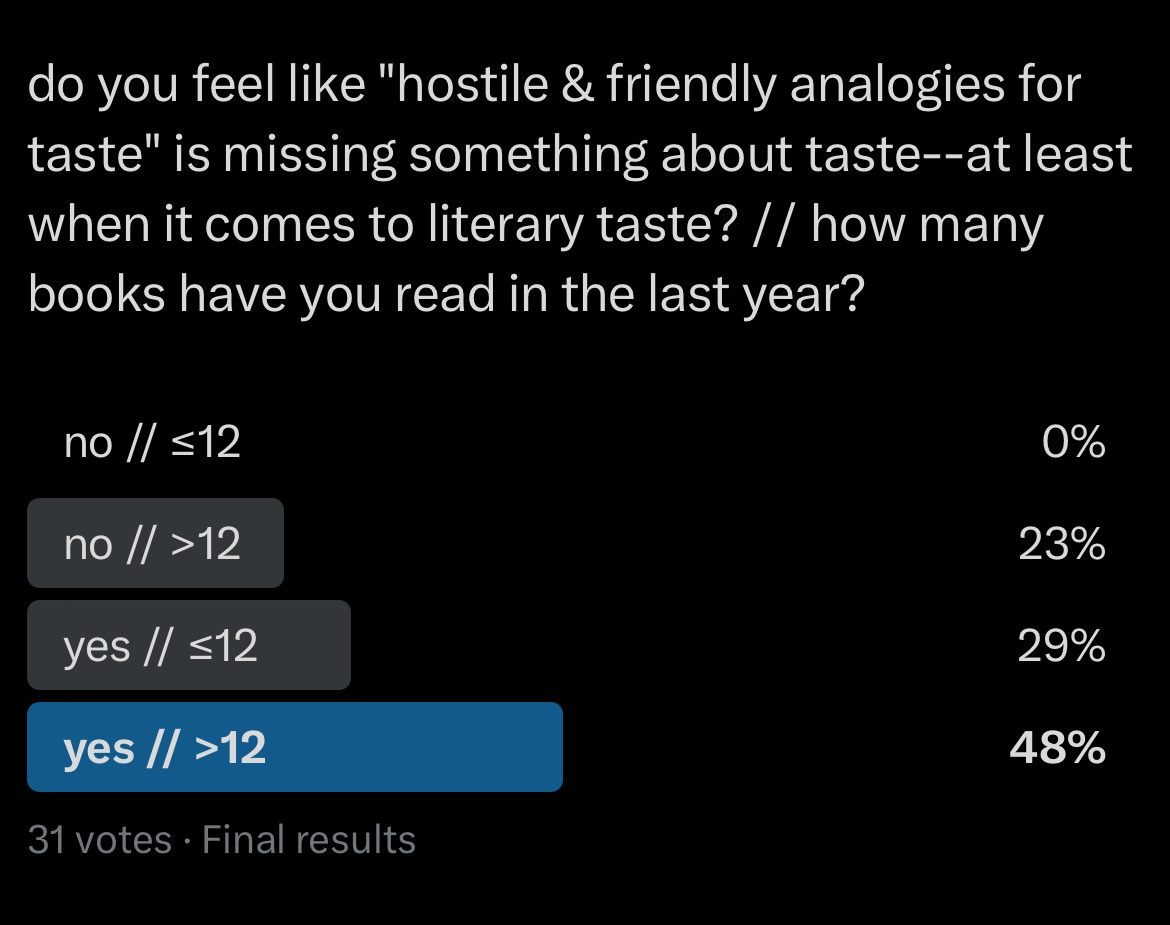

To make sure it wasn’t just me for whom “(literary) taste” and “(literary) pleasure” and “actually reading books” linked up, I ran three very poorly worded twitter polls:

The passage mentioned in the last poll comes from An Experiment in Criticism (buy it here, read it for free here), C. S. Lewis’ excellent book about exactly the question of what good taste feels like from the inside:

If we say that A likes (or has a taste for) the women’s magazines and B likes (or has a taste for) Dante, this sounds as if likes and taste have the same meaning when applied to both; as if there were a single activity, though the objects to which it is directed are different. But observation convinces me that this, at least usually, is untrue.

…the first reading of some literary work is often, to the literary, an experience so momentous that only experiences of love, religion, or bereavement can furnish a standard of comparison. Their whole consciousness is changed. They have become what they were not before. But there is no sign of anything like this among the other sort of readers. When they have finished the story or the novel, nothing much, or nothing at all, seems to have happened to them.

This book is much better worth reading than this essay. At 36k-ish words, it’s obviously longer, but not really long; you can get the meat of the argument, touching on all of the views of taste that Scott mentions—taste as arbitrary rules, taste as fashion, etc—for about 21k words by skipping the chapters on genres (“On Myth,” “The Meanings of Fantasy,” “On Realisms,” “Poetry”) and just (“just”) reading the chapters on “The Few and the Many,” “False Characterisations,” “How the Few and the Many use Pictures and Music,” “The Reading of the Unliterary,” “Survey,” “The Experiment,” and the Epilogue. 36k words and 21k words are both longer than this ~2500 word essay, so I would only expect a reader to go for An Experiment in Criticism instead of (or, as well as) this essay if that reader got an unusual quantity and intensity of pleasure from well-written text—which, like, it seems pretty clear that Scott Alexander does. That’s the bizarre thing about writing this argument: I’m arguing for good taste as a measure of the capacity for pleasure, and the person I’m arguing against seems like he has a high capacity for pleasure from text.1

I don’t want to paraphrase all the salient parts of An Experiment of Criticism, because seeing it in my own prose (so much worse than Lewis’ prose!) gives me a “visceral feeling of violation.” So I will again beg all my readers again to stop reading what I’m writing here and go read that instead. But in case anyone doesn’t want to commit to a book without knowing a little more about it—or in case anyone has the charity to read this essay anyway, even though it’s worse than the book—I’ll try to summarize from it what I need to make my argument, in as few words as possible:

Some people care much more about some field of art or human experience than most people do, because those few get much more pleasure, in quantity and intensity, from that field than the many do.

“A work of (whatever) art can be either…treat[ed]…as assistance for our own activities” or enjoyed as a thing in itself. It’s only possible to get the special quantity and intensity of pleasure from treating a work of art as a thing-in-itself; you cannot get that type of pleasure from just using it.

Not every object in that field of art is equally capable of being appreciated as a thing-in-itself.2

Good taste is usefully defined as the capacity for deep aesthetic pleasure, and the discernment to judge whether a given thing is capable of inducing deep aesthetic pleasure.3 (Bolded because this is the point of this post.) Not necessary to good taste but something that people with good taste desire and admire, is knowledge of the field they care about—knowledge of the craft and technique if it’s a field of art, but also having a general lay of the land, what there is to be enjoyed, and already knowing at least some of the things that are deeply enjoyable, and some which can be safely dismissed. The first two require some natural talent, but all three are trainable—and the training is worth it, because it allows you to get more pleasure out of the same amount of resources.4

I feel like the second and third bullet point, the appreciating-a-thing-in-itself stuff, could benefit from an example. Because reading necessarily takes time, the example will be visual. When I was in a Christian milieu, the worst visual art that I regularly saw was Christian religious art, because (people thought) it had an obvious value beyond itself, so it didn’t need to be that good-in-itself to earn sharing. Now, the people around me who care about spirituality are mostly in a vaguely Buddhist, psychedelic cluster. So the only Christian art I see is world-rendingly beautiful (because no one believes it has that much value beyond itself, so they only share it if it’s obviously valuable as a thing in itself), and the worst visual art I regularly see is vaguely psychedelic, vaguely Buddhist art.

This image has all the aesthetic value of a Christian children’s cartoon.

When I peevishly, shittily started a twitter fight about the mask picture by saying “it seems like people only find this image beautiful if they agree w the belief it expresses, which in my opinion is a sign of a bad piece of art,” people who disagreed with me said stuff like:

people are talking about it, which makes it good

it makes people feel things, which makes it good

it communicates a difficult concept, which makes it good5

Literally no one defended it by saying anything about the image itself. No one was like “Look at the lines, the composition, the colors. I could just stare at it and drink it in.” Someone described it as “evocative;” obviously beautiful things can be evocative, but the highest praise that people gave this picture is that it quickly made you stop paying attention to it and start thinking of something else.

And the people who I was arguing with about this are highly selected to be able to appreciate real beauty in an image where there’s any real beauty to be found! These are the people who see my twitter, who are selected for caring about aesthetic experiences, because I talk about this all the time. These people are selected to be meditators, who should have practice feeling the difference between paying attention to something and being led away from paying attention to it. These people are largely psychedelic enjoyers, who are high in openness to experience, which as Ozy rightly points out here, is fundamentally about aesthetics.

If these people aren’t having a direct aesthetic experience with this image, then it is just not possible to do so. This is just not an image that is capable of sustaining the continued, receptive attention that leads to deep pleasure.6

On the other hand, here’s an image also drawn from mystical experiences I don’t share, also made to express a worldview which I don’t think is true, and which rewards attention with pleasure:

Obviously, there are ways that elite taste differs from normie taste which clearly don’t increase capacity for pleasure. Scott and probably Robin Hanson describe why elite taste does this much better than I can: fashion cycles, status signalling, etc. I also think a different, tragic thing can happen where people with natural good taste go into evaluator roles where they regularly come into contact with bad work, and that contact degrades their taste in predictable ways (I kind of want to write more about this). But I feel pretty comfortable just describing all of this stuff as elite bad taste.

Close to the end of his post, Scott says,

The strongest argument for the reality of taste is the visceral feeling of violation that some people get upon seeing tasteless work.

Not at all! The strongest argument for the reality of taste is the deep pleasure that some people get upon seeing beautiful work.

I actually started reading Unsong while working on this post just to double-check. (Perverse incentives—hey everybody, post something that annoys me and I might read your novel!) I’m 90-odd pages in, I don’t know if the book is going to succeed, but it’s obviously aiming at a deeper and more intense experience than, like, Colleen Hoover.

But if you can appreciate it as a thing-in-itself, that doesn’t disqualify it from being used as a conduit to other things—although it’s hard to do both at the same time.

I feel like a lot of people think reading great literature is morally improving. I don’t really think this. It usually feels morally improving while you’re doing it, and sometimes it is—sort of like how psychedelic drugs make you feel like you’re having great insights when you’re on them, and sometimes you are. But I have not noticed that the well-read are particularly good people. Who knows, maybe we’d be even worse if we weren’t well-read.

I’ve often thought it’s really weird that “utilitarian” means both “aiming for the greatest good for the greatest number” and “not aiming for beauty.” Although the love of beauty, like all passions, often tempts people to treat others wrongly, it’s also true that beautiful things are capable of giving more pleasure for the same amount of resources. Well, making beautiful things usually needs more work, but people tend to enjoy that work more than the work of making quote utilitarian unquote things.

And then a subset of those people tried to explain the concept. Look, I get what the picture is trying to say. I’ve done psychedelics, and I’ve done more than my share of meditation over many years. I just don’t find this idea particularly compelling or useful. In the interpretation I could possibly agree with, which is pretty narrow—“avoid calcifying yourself in your self image”— the vaguely Buddhist psychedelic way of talking about it isn’t a good pointer for me and I’d rather read the Last Psychiatrist. In the most ambitious reading, I think it risks active harm. Sure, maybe I would agree with it if I tripped more and meditated more, but I’ve done enough of both to suspect that they often give you the feeling of discovering existing things which they are in fact creating (or, in this case, that meditation/tripping often feels like finding absences when in fact what’s happening is that something is being destroyed). To me, this seems like putting a microphone next to a speaker in an attempt to amplify the true base sound of the universe, and deciding that the music of the spheres is feedback screech.

I don’t know why some art is conducive to deep pleasure and some is not. I don’t know if it’s something about the human brain structure; I’m embarrassingly tempted to platonic aesthetics by stoned-freshman questions like “Why do humans also love the smell that flowers create to call out across a genetic gulf to insects, even though we’re just eavesdropping on the flower/pollinator love affair?” and “Why are highly sexually selected birds so beautiful to us? Why do we literally watch hours of bird mating dance footage on shows like Planet Earth, like we’re femcel birds with a porn addiction?” and “Why do aesthetically good things work better? I’ve noticed that a lot of people try to eat healthily with zero attention to the aesthetics, and it’s really hard for them; for me a really healthy meal feels in certain ways more like looking at good art than it does like eating chips, and I’m also pretty healthy. What’s up with that???” But I also recognize that this is some real stoned freshman material, so I’m not wedded to it.

This is really great and resonates with my experience of music. I've described it as sometimes being intense and psychedelic, like waves of intensity flowing through my entire body, and sometimes I get sad about not being able to share that experience with anyone, but it's meaningful on its own anyway.

Your post reminds me J.S. Mill's arguments for qualitative differences in pleasure in "Utilitarianism." I'm skeptical of the argument in your post for similar reasons that I am skeptical that Mill's argument really works.

Mill says that Good A is "qualitatively better" than Good B if all or almost all individuals who are experienced with both goods would choose Good A over any quantity of Good B, independent of any feeling of obligation towards either choice. (He is arguing against Bentham, who claimed that all goods are comparable (and can be reduced to pleasure), famously saying "if the quantity of pleasure be the same, pushpin [children's game] is as good as poetry.")

For example, Mill argues no human would give up their life for that of the most pampered pig. Hence, “enjoyment of human cognitive faculties” is qualitatively superior to “pig pleasures.” He says that if the pig disagrees, this owes only to its ignorance of the alternative.

Mill recognizes that people regularly choose lower pleasures over higher ones (a problem for his view). However, Mill argues that all such instances occur out of akrasia, and those who choose lower pleasures over higher never do so willingly. (He compares a love for the arts to a tender plant that can easily die, but which no one would willingly let perish.)

I think this defense doesn't work. First, though humans may not prefer to be pigs, it is a non-sequitur to conclude that pig existence is therefore less “pleasurable.” Mill must argue further that humans could not prefer something that does not maximize pleasure.

Worse, even well-educated individuals who have experienced the joys of intellectual pursuits and liberty regularly reject them in favor of hedonistic or materialistic pleasures. If Mill intends to dismiss these widespread choices as unwillingly made, and thus irrelevant in the calculus of qualitative pleasure determination, Mill must answer in what sense they are “unwilling” (evidently they are not *coerced*). I do not think he can provide a good reply; yet, without an independent explanation of which choices are made willingly, Mill is simply inconsistently applying his criterion of recourse to human preference for determining qualitative difference in pleasure.

Along these lines I'm skeptical that it really makes sense to say that people who appreciate great art (say, reading Hamlet) are really experiencing greater pleasure than people watching WWE.

The most mundane reply seems to me to be to say that people are value pluralists, and value more than just pleasure. Drinking or playing video games might be more pleasurable than reading Hamlet, but I'll read Hamlet anyway because I think it reveals profound truths about human life, and (as a very weak statement) I prefer spending some time learning deep truths about human life over spending all of my time on pleasure.

A more interesting line that I'm open to is that reading Hamlet can be a transformative experience, a la LA Paul (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transformative_Experience). That is, it is hard to imagine before reading Hamlet really what it will be like, and it is hard to reason about the decision because it is likely to change your values. There are elements of this idea in your CS Lewis quote.

I think that reading Hamlet is a lot like having children. Adults with minor children in the house report lower moment to moment happiness, and plausibly less "pleasure" than nonparents. However, parents report that they believe their lives are better along dimensions other than moment-to-moment happiness (e.g. more meaning / purpose), which supports my argument that people are value pluralists. Furthermore, having children drastically changes your values (both from interviews and MRIs, which show that having kids changes fathers' brains), and is a classic example of a "transformative experience."